“Memory is the paradise from which you can never be removed”, writes Leni Riefenstahl in one of her diaries, part of the mass archive that makes up Andres Veiel’s documentary. On this particular occasion, she is referring to her work with Arnold Fanck on mountain films such as The White Hell of Pitz Palu which, despite the numerous torments endured, including being engulfed in avalanches and climbing rocky pinnacles barefoot, were no doubt some of the happiest and least controversial times of her life. They were also no doubt the lesser known. Riefenstahl, first and foremost, is renowned for her work on propaganda during the Nazi era, and her assertion, in the years that followed, that she had not known at the time what the films would be used for or what supposedly close friends Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels were planning. Memory, in her case then, is a far cry from paradise.

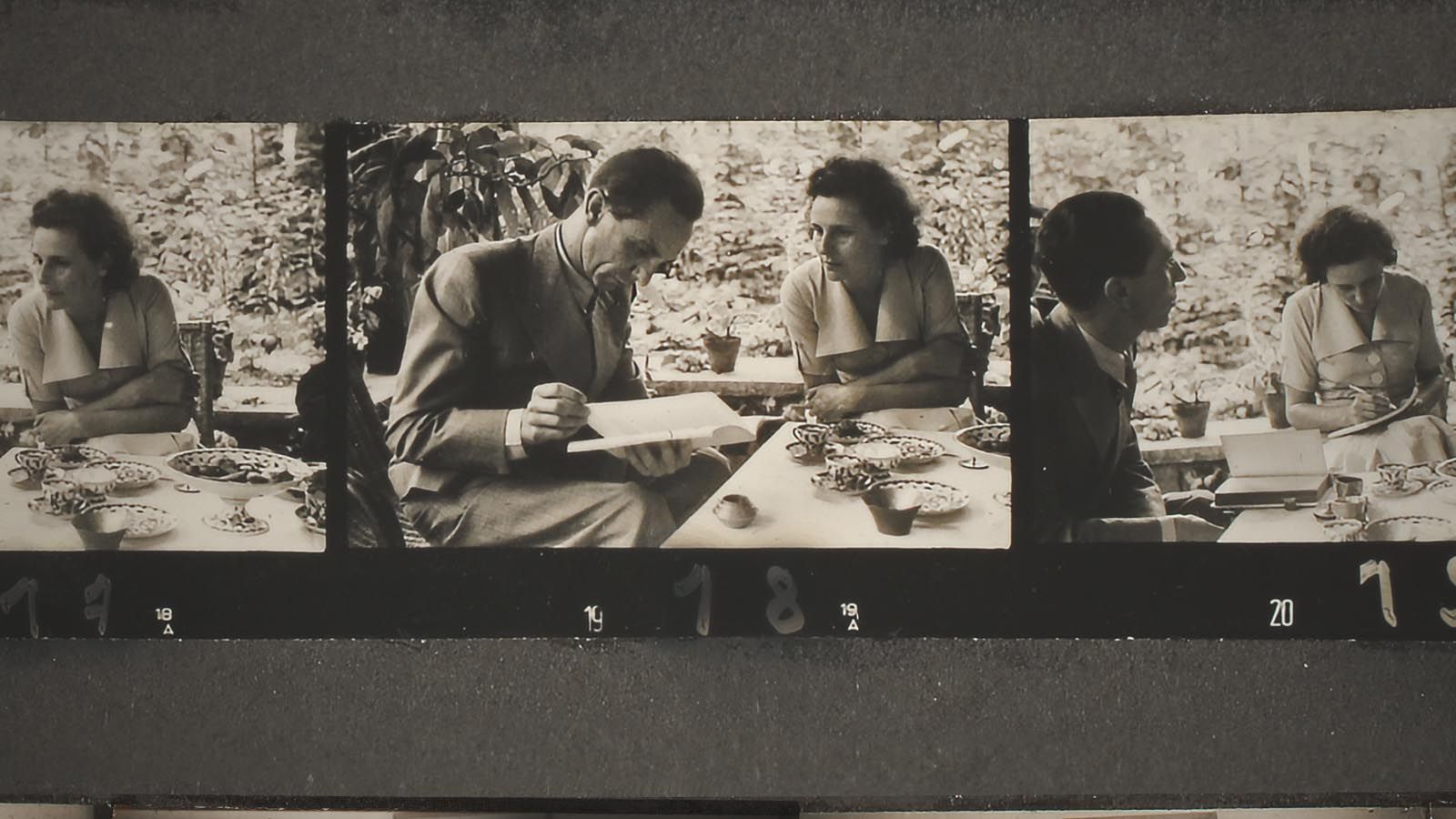

In just under two hours, Veiel takes us from the beginnings of Riefenstahl’s career through to her old age, with the material from her estate which included 7,000 boxes of scripts, letters, film excerpts, photographs and recordings. Fleshed out by his team of editors, it tells a very complex story of a woman caught in the web of the Nazi regime (or was she participating in its weaving?), and the aftermath of her actions once the war was over. In an early interview, she states that she was naïve, that politics and art cannot coexist, and that she had simply “been asked” to make the films, the most famous of which include The Blue Light, Triumph of the Will, and Olympia, a documentation of the 1936 Olympics. She did not know what they would be used for, she said. What would you have done in her place? I wouldn’t have done it, a woman she is being interviewed with on live television insists in a particularly treacherous conversation. It’s cutting, uncomfortable – Riefenstahl protests: they did not know what was going on. No one in their right mind could claim this was true, the woman answers. The response post-air is astonishing: Riefenstahl receives fan mail, phone calls thanking her for her bravery in speaking out on national television. Is it collective shame, a cult of personality? Do people see a voice in Riefenstahl, are they admirative of her outspokenness? Never does she try to defend herself with claims that she was too scared to say no. She was asked and, quite simply, she did what she was told.

Riefenstahl is no doubt a fascinating character (her memoirs are strangely difficult to get a hold of), and a perfect subject to study via documentary. Her mannerisms are bizarre, her thought process inexplicable – she is, in all manners of the word, unreadable, either too clever for this world or extremely naïve, as she claims to be. Veiel gives us a good summary considering the vast amounts of material to work with, though the final era of the war is a little too glazed over and, on a rather superficial note, the voiceover choppy and ill-fitting. The real issue with Riefenstahl is its inherent bias, its painting of its subject as someone at times almost devil-like. At one point, photos of Riefenstahl circulate onscreen, the final one toned red, left lingering, zoomed in slightly to eerie music: it is almost like a set of horns is being painted onto her head. The choice to cut at certain times is a little too transparent in this sense – an interviewer asks a particularly difficult question, and Riefenstahl, now aged on her sofa, pauses to think. We never get to hear her answer, but Riefenstahl has done enough by suggesting what should be left to the imagination. Her memory in this documentary remains a little too black for someone who was famously characterised by history as grey.