“Very, very tired”, Steve breathes when he is asked to describe himself in three words by a television crew documenting the reform school at which he is headmaster. This is just one of the tasks he must address on this particular day at Stanton Wood – there is also the day-to-day behaviour of the troubled boys he must take care of, including the evident decline of one of his best pupils, and the fact that the trust has just announced they plan to shut the school down within six months. Tense and overstimulating in the most effective of ways, Tim Mielants’ drama is the clever portrait of a man at the end of his tether – and a very real question mark around the role reform schools play in modern society.

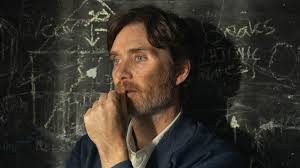

As Steve, Cillian Murphy is remarkable, a force of nature – we catch him on his commute to school, where he stops to find Shy (Jay Lycurgo), the aforementioned pupil, smoking weed and dancing in the middle of a field. There is good rapport between Steve and Shy, and it is noteworthy that Max Porter’s novella, on which the film is based, was originally named after the latter. That the team behind the film swapped the title to focus on the headmaster instead points to the increasing need to highlight the caregiver rather than the recipient – together with deputy (Tracy Ullman), fellow teachers and therapist, Steve must devote his time, efforts, and energy to these boys, complex beings as he calls them, stopping fights here, calming those who are upset there. He does not have time for a documentary to be filmed in his hallways – and it is something that the crew take great advantage of, filming his students without his consent, and even going so far as to snoop around in their bedrooms, laughing at some of the boys’ most treasured possessions. On camera, the presenter ponders whether the school is taxpayers’ money being washed down the drain or a genuine effort to reconvert the troubled into valuable members of society. In the next scene, a virulent fight breaks out, and Steve must pick up the pieces. It is not long before he begins to falter.

Robrecht Heyvaert’s cinematography is tender, and flexible when it needs to be – in the heartfelt moments, it gently focuses in on eyes, mouths, nervous tics, yet it does not shy away from capturing the gritty reality of chaotic fights, particularly prominent in a scene in which two boys fight across the cafeteria and kitchen. It is Shola (Little Simz), the quiet new teacher, who shuts it down with a guttural scream, at which point Heyvaert angles in on her face, signalling the end – or so we think – of disorder. At Stanton Wood, it becomes clear that everything is a battle, and clearer still that there is no “right” way of handling such unpredictable personalities. As designated cool teacher, Steve has no qualms telling Shola that none of them truly know what they’re doing – he says things to calm the boys, only for it to blow up in his face. Everywhere the staff must walk on eggshells, for fear of saying the wrong thing and seeing weeks of hard work snap before them. In parallel, Mielants is quick to highlight Steve’s own repressed trauma, one he now uses as fuel for the greater good. The film in this sense poses the important question as to who is truly equipped to deal with the troubled, if everyone is troubled to a certain extent? Is it enough to simply care? Because Steve cares, a lot. It is palpable, present in his eyes, in his mannerisms. As Amanda says, she is mother, therapist, punching bag, and more – but she absolutely loves them with all her heart. Like Amanda, like Steve, it is easy to fall in love with these boys, big hearts and personalities incapable of controlling their emotions, yearning for love but reticent to show any signs of weakness. The audience’s omniscience in a story in which everyone could falter at any second, but no one is willing to open up, is what makes Steve particularly sad. It is Jenny’s words to Steve here that resonate the most: “you can’t do it all”.