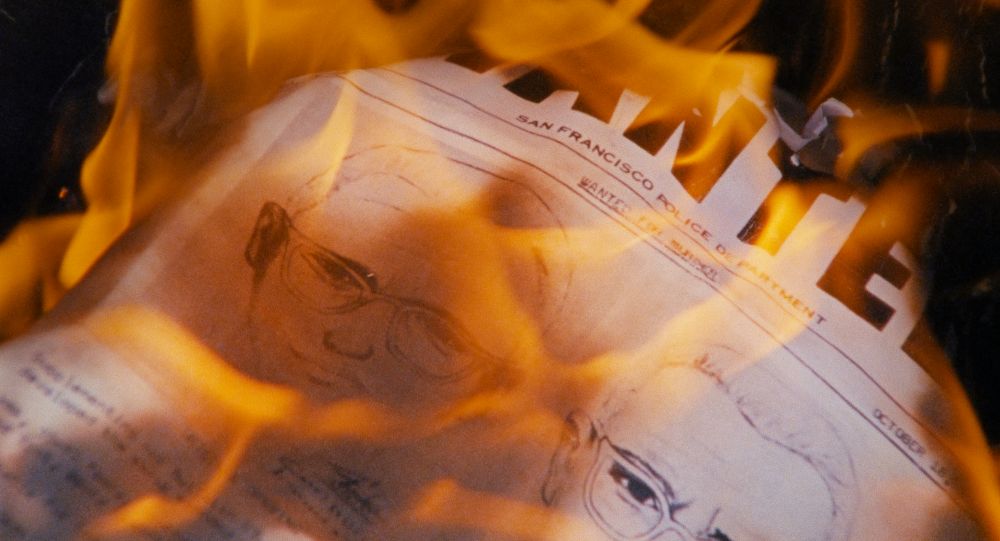

Charlie Shackleton was halfway through planning his Zodiac Killer documentary when the rights to the source material fell through. What could have been another failed project quickly pivoted into something new and refreshing – a documentary about the documentary, had it been made. In an hour and a half, Shackleton, who acts as guide and voiceover, walks us through what his project would have looked like, from the facial expressions of the actors he never cast through to the locations, some he had planned to use, some he hadn’t, where the action would have been set. Along the way, he questions the increasingly commercial genre that true crime has become and the all-time puzzling case of the Zodiac Killer, who – for those who haven’t seen the David Fincher film – was never found. What About Birdy sat down with him to discuss his thoughts on our fascination with the macabre, spontaneity and how failure can be turned into creativity.

WAB: Where did your interest for the Zodiac Killer first come from?

CS: I don’t remember exactly when I first became fascinated by it, but it was probably as a teenager watching the David Fincher film. I remember after that having this sort of ambient fascination with it and doing my own amateur sleuthing online, reading about all the various different theories and people’s evidence that they’d amassed over the years. Long before I got into documentary I was interested in the case and then when I started working in documentary, it occurred to me that there wasn’t a definitive doc on what is one of the most, if not the most famous, cold case of all time.

Q: What do you think is the story’s relevance today?

CS: The interesting thing to me about the Zodiac Killer is that he’s second only perhaps to Jack the Ripper. He’s the first serial killer slash publicist, and he made it his own. He literally gave himself his own nickname and built this lore around himself, which is probably the only reason people are still talking about him. In terms of actual crimes, there aren’t all that many compared to more prolific, more horrific serial killers. But he was very good at keeping his name in the newspapers, and I think that has informed and structured a lot of true crime lore in the decades since. To me, it seemed like an interesting case to look at in order to think about true crime more broadly.

Q: You mention that true crime has a “gravitational pull and that you eventually give in to it”. How much of it is performative?

CS: It’s funny, a lot of people who watched the film were surprised by how flippant I am about quite serious subject matter. But I think if you work in that world, you can’t help but become a bit flippant. The difference between doing something sincerely and doing it performatively is a little grey, because we’ve all seen enough true crime content that we have absorbed the tropes of it, whether we know it or not. Half of the time, you’re doing something completely sincerely and then you realise that you’re doing the same shot again and again and again. You can be doing it entirely earnestly but still unwittingly replicating a trope or formula. In the same way, they wouldn’t be tropes if they weren’t effective – a lot of the time they are useful shorthand to get an audience into a certain headspace or convey an idea without having to go beat by beat through every little marker of it. You can be performative and sincere at the same time in any genre, especially one that is totally saturated like this one.

WAB: On the topic of sincerity, did you have a script or did you ad lib the commentary? What was it like performing in a film that you likely would never have been in had you gotten the rights of the book?

CS: It was all improvised. I had made films before where I’d narrated them in a conversational style but I’d always scripted that narration. To my ear, I could really hear the falseness because I’m not an actor. With this film, I set myself the challenge of not scripting any of it because I really wanted that spontaneity, that feeling of how someone organically, conversationally telling a story. So when I went into the recording booth, I had reams and reams of notes, bullet points, and from there I ad-libbed. Obviously, there’s a lot of editing to make it coherent and bearable to listen to! If it feels like there were a lot of ums and ahs in the finished product, there were three times as many in the original recordings. It’s certainly a little massaged.

WAB: I think you certainly achieved that conversational tone, I answered one of your questions halfway through and forgot I wasn’t speaking with someone live.

CS: I actually was in a recording studio though, looking through glass at my producers. So I was talking to someone. There’s this feel of rhetorical questions, but half the time they were actual questions to real people. But a lot of the time, when I’m listening to it, it’s like I’m just talking to a void, especially when I laugh. It really divides the audience when I laugh at my own jokes.

WAB: What role does the audience have to play in this film and in true crime as a genre?

CS: It’s something I come back to a lot, and something that the true crime industry is constantly wrestling with: why do people want to watch this material? But to me, that question has become less interesting than the question of why we, as an industry, are so invested in producing this material, in creating supply regardless of demand. It’s just as likely that the supply is what’s driving the demand – you load up any stream and you’re presented with a bunch of true crime options. And obviously, when you watch one, all the others are suggested to you. There’s this preternatural desire for this really macabre content. But it’s easy to repeat the formula, any real life crime can fit into this pretty plotted narrative, and therefore be churned out reliably.

WAB: Like those influencers on Instagram who teach you how to create a trailer for a true crime film, with the eerie voiceover and the lightbulb. Zodiac Killer Project is almost meta in that sense.

CS: Yes, and there are even viral AI channels now where the crimes are completely invented, but they’re presented as true crime. So they’re not only fiction but fiction made by AI, and are now often fairly indistinguishable from real life cases. I made the film a year ago and there are already whole new angles of grim reproducibility emerging.

WAB: You mentioned in an interview you did for Paint Drying that you liked to work with limits. The whole point of Zodiac Killer Project is that you didn’t get the rights to the book even though you were halfway through plotting and scouting locations. Until you found the antidote, which was this film, what was the grieving process like?

CS: At first, I was obviously very disappointed. It wasn’t the first time that I’d had a project fall apart fairly far into the process. It’s pretty routine in documentary, so I thought I would just lick my wounds for a month and move on. But in this case, I had made the mistake of conceptualising the whole thing more than any previous failed project, even though I hadn’t done much actual work, spent much money, created any visual material. I just found myself reliving and recycling the imagined sequences, so the form of this film of me describing a scene beat by beat was already happening on a freelance basis in real life – I’d be in the pub with a friend explaining how this would have happened, and how that would have happened, the audience would have felt this way, and then we would have had this shot of the fishbowl, and it was only after a month of doing that, that I realised that maybe this in itself was an idea for a film about creative frustration and failure. So I’m glad in the end that I didn’t get over it.

Zodiac Killer Project screened at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.